About Tim.

Painting came to me later in life. Like any creative pursuit, painting requires a real commitment in terms of time and energy and for many reasons I was unable to commit. Instead I dabbled infrequently, almost always during vacation, and any success was easily discouraged by a harsh inner critic. However, the urge to pick up paints and paper never completely disappeared, and when I reached my late sixties more opportunity came my way.

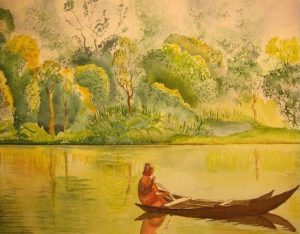

Serenity on Water, India

by Tim Barraud

The incongruity of denying myself the one thing that gave me the greatest satisfaction started to haunt me. I was haunted also by the words of a psychic I visited with during my forties; she told me she had concerns for my heart if I failed to fully embrace the artist within me. Two decades later, during a workshop involving soulful choices, I committed to creating a simple studio and spending time there every day for thirty days ⏤ and i did this.

Another important step was moving my desire to paint from the bottom of my “to do” list to the top. Painting became a habit, an easy choice, and I was rewarded by a steady growth in my skills. I now receive daily pleasure in viewing the best of my paintings, framed and hanging on the walls of our house.

It also helps me to know that the creative impulse has been in the Barraud family for many generations.

HMV Emblem

by Francis Barraud

My ancestors were Huguenots who fled oppression in France by migrating to England in the seventeenth century. Many were artisans who established themselves as clock and watchmakers and as painters of animals in the south of England. William and Henry Barraud were brothers who collaborated on their paintings of horses, dogs, and livestock; their paintings have long been collector pieces. Perhaps most famously, Francis Barraud immortalized Nipper, his white-and-tan Jack Russell terrier, with his head cocked, listening to his master’s voice through a phonograph. This painting became the emblem adopted by the record company HMV, His Master’s Voice.

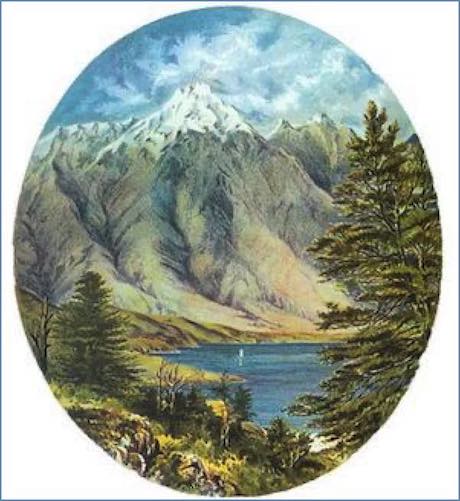

My great-great-grandfather, Charles Decimus Barraud, tenth-born of twelve children of William Francis Barraud and brother of William and Henry the animal painters, migrated to New Zealand early in the nineteenth century and established himself as a pharmacist in Wellington, the capital city. From there he painted prolifically, recording early New Zealand life while traveling extensively on horseback. His paintings and lithographs of Maori life and early New Zealand landscapes can be viewed in museums and galleries. His son Noel, who founded an early stock and station agency called Barraud and Abraham, was also an artist. Many of Noel’s landscape paintings of New Zealand and Europe have survived and are valued as collector pieces.

The Remarkables

by C.D. Barraud

One afternoon, my eldest son Ben, head of design at the Te Papa museum, an imposing building on the waterfront of Wellington harbor, took me down into the chilly, climate-controlled archives below the Te Papa, where much of New Zealand's past history is stored. With the assistance of a manager, we pulled out paintings by C. D. Barraud and viewed many of his original works of art. I felt the thrill and connection of deep heritage and family history.

There were other Barraud artists in New Zealand who descended from C.D. Barraud, one of them being my father, John Slingsby Barraud. He graduated from Elam Art School in Auckland before being swept away to fight in World War II. After the war, he made his living as a portrait photographer in Wellington and later as a cultivator of quality carnations, which he shipped all over New Zealand. On weekends and holidays, his easel and painting gear were never far away, and occasions such as picnics, usually by a river, found him staring off into the distance and then back at his easel as he created one of his many landscapes painted in oils and water colors. His paintings hang on my walls and the walls of my two brothers. A rich heritage, indeed.

The "curse of the Barrauds" is how my grandmother referred to the artistic talent and where it landed; she was referring to the difficulty of using this talent to make a living and also raise a family. However, my youngest son, Arnaud (Ned), came into the world with this talent and was busy drawing, whatever was in front of him or created in his mind, from a very young age. I warned him of the curse and how he needed to broaden his options in terms of career but off he went to art school. Today, he and his wife Niamh are raising a delightful family of three, and Ned is very much the artist. During the day he works for Sir Peter Jackson at Weta Studios in Wellington, where he has been integrally involved in the creation of many movies, including the Tolkien Trilogy: The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. At night, he stays up late and illustrates a wonderful and successful series of children’s books that bring to life the flora and fauna of New Zealand. His books can be viewed at NedBarraud.com.

As a growing boy, I was inescapably influenced by this family history. In the different houses in which we grew up, my brothers and I looked up at reproductions of C.D. Barraud’s paintings hanging on our walls as well as our father’s landscapes and a few scenes of horses and hounds painted by ancestors.

Growing up, I often wondered if the family gift of art would be visited on me. But it was my older brother Arnaud who seemed to have the motivation and skill, so I looked for other talents and pursued my love of animals, which eventually led to my career as a veterinarian. Arnaud eventually became a ceramic artist ⏤ a potter. He lives in the hills set back from Melbourne, Australia and has been turning out first-class domestic pottery for fifty years. He is another exception to our grandmother’s rule ⏤ "the curse of the Barraud’s" ⏤ and sells his ware at various weekend markets. In this way, he has supported his family all his working life and at 78 has no plans to retire.

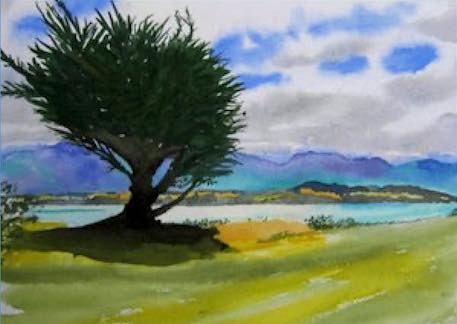

Lake Ferry, Southern New Zealand

by Tim Barraud

However, one experience involving art lodged deep within me and helped lead me to my current pursuits. When I was 15 years old, we were on a family holiday beside a southern lake on the South Island of New Zealand. One late afternoon, I put together paint and brushes, borrowed watercolor paper from my father, and found my way down to the lakefront. Here, in total isolation from family and other humans, I stared across the lake as setting sun lit up the world and applied paint to paper, creating a primitive image of lake, sky, and mountains. I became totally absorbed and lost within the experience.

From this occasion I have retained the memory of a warm and transcendent union with nature, evoked by the act of creation.